Donald Trump shocked Wall Street with his surprisingly strong stomach for the stock market plunge that his tariffs precipitated .

But although wiping $10 trillion (£7.8 trillion) off global share prices in a matter of days apparently failed to rattle the US president, he was no match for all out market Armageddon.

Just as the UK’s former prime minister Liz Truss was forced to reverse her unfunded tax cuts after a bond vigilante rebellion in September 2022, Trump has suddenly about-turned on his “reciprocal” tariffs in the face of a looming global financial meltdown.

In a surprise post on his Truth Social account on Wednesday, Trump announced a 90-day pause on the individual reciprocal tariffs on America’s trading partners that have rocked financial markets since he unveiled them on April 2.

Instead, all countries will be subject to only the minimum 10pc charge he had set for all of America’s trading partners. That is, all countries except China, where he ramped up tariffs even higher – to 125pc.

The enormous row-back shows that even Trump has to bow to markets and what had become a tidal wave of criticism as economists sounded huge alarm bells over an imminent recession and financial crisis.

Trump might have played it down, but he could not deny that his big problem was bond yields.

“The bond market is very tricky. I was watching it ... I saw last night where people were getting a little queasy,” Trump told reporters on Wednesday afternoon.

Queasy was an understatement .

Normally, interest rates on government debt go down when stock markets fall. If investors sell stocks, they typically want to move their money to safe-haven assets, which drives up demand.

This time around, the opposite happened. Instead of buying, investors embarked on an incredibly aggressive sell-off.

When investors sell bonds, demand is falling. This means that buyers can command higher interest rates, so yields rise.

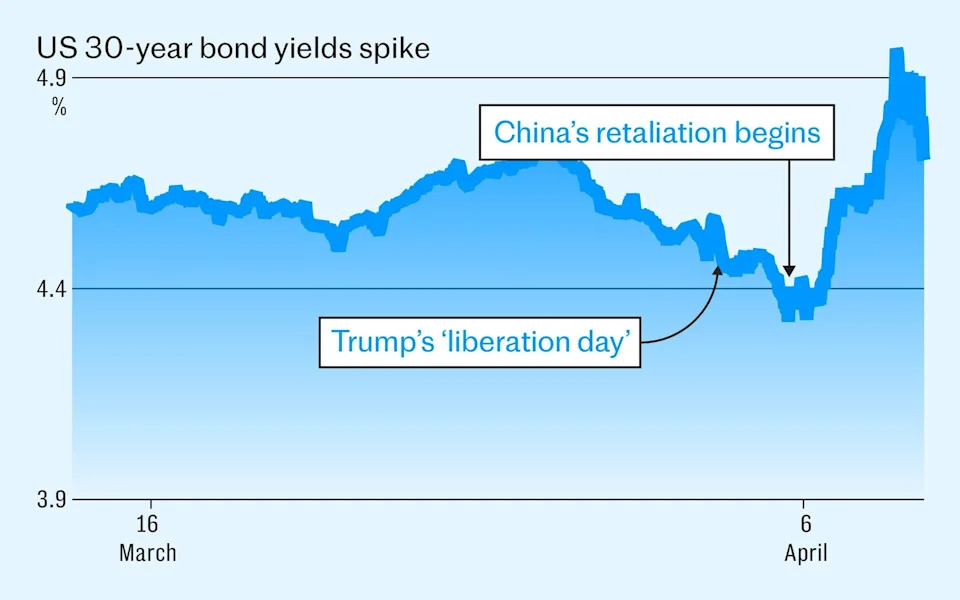

Since Trump’s tariff announcements, demand slumped so much that, in just two days, yields on 30-year US Treasuries rose at the fastest pace recorded during any major stock market downturn since 1982, according to George Pearkes at Bespoke Investment Group.

In the week after Trump announced reciprocal tariffs, up until his about-turn, yields on 30-year US Treasuries had rocketed by nearly 40 basis points, rising to 4.91pc, while yields on 10-year debt had jumped by around 0.3 percentage points to 4.45pc.

At the same time, the dollar – another safe-haven asset that would typically strengthen on recession warnings – tanked. The dollar index has plunged by 3.4pc since the start of March. “The market is rapidly de-dollarising,” George Saravelos, head of FX at Deutsche Bank wrote in a client note on Wednesday morning.

Investors have been shunning all things American. “We are witnessing a simultaneous collapse in the price of all US assets including equities, the dollar ... and the bond market,” Saravelos said.

“The market has lost faith in US assets.”

An auction for three-year US Treasuries on Tuesday received a weak response, exacerbating fears about demand. And while an auction of 10-year bonds on Wednesday was well received, the proportion sold to direct buyers, namely banks and hedge funds, plunged to one of the lowest shares on record.

If the disruption had continued, the Federal Reserve would have been forced to intervene to make emergency mass purchases of US Treasuries to stabilise the bond market, Saravelos warned.

In other words, it would have had to do exactly what the Bank of England did during the gilt crisis that followed Truss’s mini-Budget in September 2022.

Larry Summers, a former US treasury secretary, warned on Wednesday morning that the market movements meant “we may be headed for a serious financial crisis wholly induced by US government tariff policy”.

The Bank of England warned on Wednesday that Trump’s trade was making the world more exposed to a financial crisis. The Bank’s Financial Policy Committee (FPC) said the steep rise in global tariffs meant “the probability of adverse events, and the potential severity of their impact, has risen”.

“Risks associated with debt sustainability concerns, including sharp increases in government bond yields , could crystallise relatively quickly,” the FPC said.

But even more significantly, Trump was grappling with massive criticism from people he could normally bank on for support.

Bill Ackman, the billionaire hedge fund boss and previously a Trump backer, earlier this week turned on the president, warning that his tariffs risked an “economic nuclear winter”.

Indeed, Ackman seems to have been the origin of Trump’s 90-day pause – he had urged the president to “call a 90-day timeout”.

Elon Musk, the Tesla chief executive and the president’s “first buddy”, said he wanted a zero-tariff free trade zone across the Atlantic and called Peter Navarro, Trump’s trade adviser and tariff architect “dumber than a sack of bricks”.

Dedicated Maga supporter Ben Shapiro broke ranks to say that tariffs were “probably unconstitutional” and “pretty crazy”.

Crucially, Rupert Murdoch’s Fox News had apparently turned against Trump’s tariff policy. The president’s favourite TV channel had started airing criticism from the likes of JP Morgan boss Jamie Dimon as well as telling the stories of businesses that are bearing the pain of higher import costs.

The parallels with Truss’s September 2022 blowout could have become even more sinister.

Back then, soaring yields on UK government debt pushed pension funds to the brink as they had to sell gilts, which were falling in value, to cover their margin calls. This time around, there is another major risk to the financial system from soaring Treasury yields.

Speculation is mounting that hedge funds are unwinding so-called basis trades. This is a scenario that analysts – including officials at the Bank of England – have been warning could cause financial meltdown .

Hedge funds buy US debt and then sell on futures contracts based on the Treasuries to investors, namely pension funds, meaning they exploit small gaps in pricing to make money.

There are two problems with this strategy. The first is that, to do this, they use short-term borrowing from banks, which is secured on the government bonds that they own. The second is the scale at which they have done this – basis trades hit a new high of $1 trillion last autumn.

If the value of US Treasuries tank, there is a massive risk to the global financial system.

Higher borrowing costs are also piling pressure on the £8 trillion private equity sector, warns Simon French, the chief UK economist at Panmure Liberum.

“The big losses suffered by banks and other money managers means investors are fearful that high interest rates and falling asset prices are a toxic combination for private equity,” says French.

If companies’ private equity backers go down, so do the companies.

“The risks are real. Two days ago, it looked really bad. That made me think, wow people are really not going to the dollar and dollar assets,” says Marcello Estevao, chief economist at the Institute for International Finance.

“Maybe this erosion of the dollar is going to start sooner rather than later. If that is the case, then the risk for a financial crisis is really strong.”

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph free for 1 month with unlimited access to our award-winning website, exclusive app, money-saving offers and more.